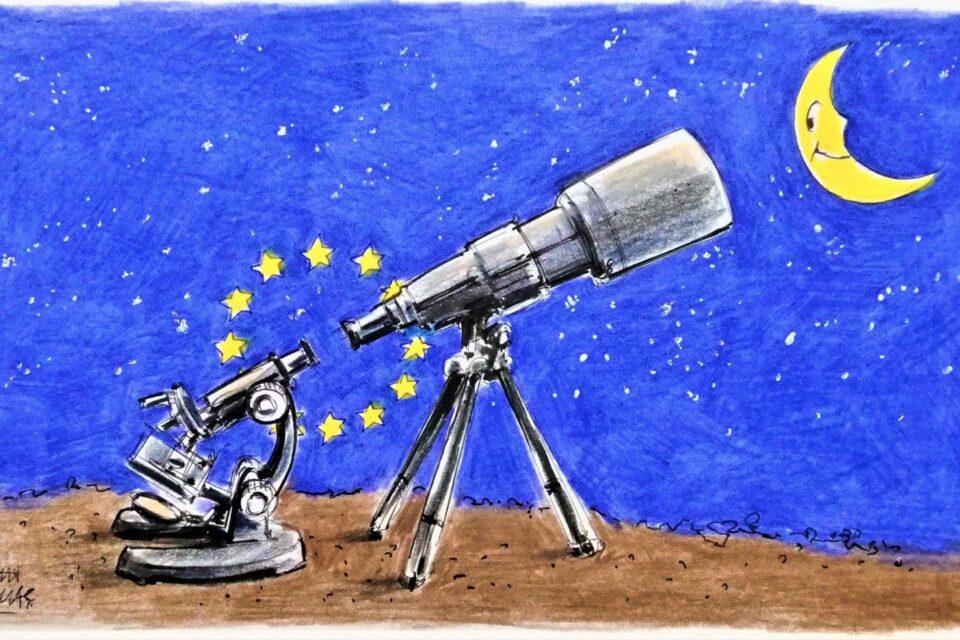

A new chapter in Turkey-EU relations?

The dangerous escalation in the Eastern Mediterranean has given way to dialogue and negotiations.

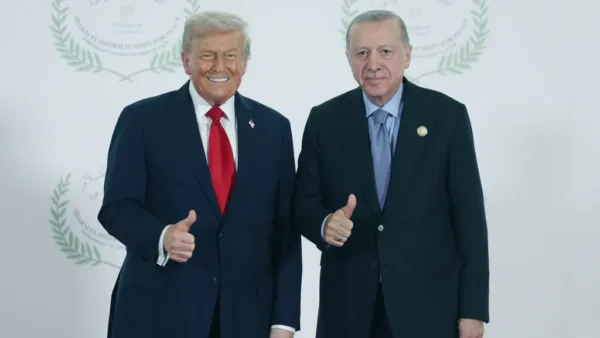

On Sept. 22, President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan spoke with his French counterpart Emmanuel Macron following a trilateral meeting with German Chancellor Angela Merkel and European Council President Charles Michel. The following day, exploratory talks between Turkey and Greece became possible as a result of Erdoğan’s phone calls with European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen and NATO Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg.

Merkel’s commitment to repairing the European Union’s relationship with Turkey, in her capacity as the Council of the European Union’s current president, along with Erdoğan’s appreciation of that effort, made serious contributions to the dialogue. Macron’s failed attempt to position the EU against Turkey, in the name of European solidarity, too, helped sway the parties in favor of dialogue.

Indeed, most European leaders do not agree with former French President Francois Hollande, who claims Turkey represents “the single greatest threat to Europe.” Eastern European governments are primarily concerned about Russia’s growing influence over the continent and the refugee crisis. Southern Europeans, in turn, know that they need to work with Turkey on Syria, Libya, the Eastern Mediterranean and energy. In their view, the Austrian proposal to terminate Turkey’s accession process threatens their interests. Again, Southern Europeans do not appreciate Greece or the Greek Cypriot administration’s attempts to hijack the EU’s foreign policy.

Diplomatic efforts, which gained momentum following the research vessel Oruç Reis’ return to port for routine maintenance, not only de-escalated tensions between Ankara and Athens but also provided a window of opportunity to mend Turkey-EU relations.

What Turkey and Greece need to do, as a first step, is to ensure that the ongoing exploratory, political and military-to-military talks lead to a comprehensive negotiation. From the unlawful remilitarization of the Aegean islands and the situation in Western Thrace to Cyprus and maritime jurisdictions in the Eastern Mediterranean, they must tackle all of their bilateral problems. Here is what the Greek government must understand: If Turkey actually turns its back on the EU, Greece will experience more serious problems as a frontier state. The pressure to beef up the Greek military will further weaken its economy.

To transform the Aegean Sea and the Eastern Mediterranean into a “sea of peace and sharing” serves the interests of Turkey and Greece alike. Needless to say, that won’t be easy.

The European Union must keep in mind its long-term strategic interests to support Turkish-Greek dialogue. Portugal, which will take over the Council’s rotating presidency in January 2021, ought to follow in Germany’s footsteps and commit to repairing Europe’s relationship with the Turks. If there is a firm commitment, we will have a nine-month window of opportunity.

Some of the issues that we need to tackle are as follows: Updating the EU-Turkey Customs Union agreement, revising the refugee deal, visa liberalization and an international conference on the Eastern Mediterranean.

Michel made the initial proposal for a conference, which Erdoğan supported in his address to the United Nations General Assembly: “We propose that a regional conference be held, which will include the Turkish Cypriots, to look out for the rights and interests of all countries in the region.”

Europe’s political leaders now have a responsibility to work with Turkey to build on that idea of a regional conference. That would be the best way to demonstrate that the Eastern Mediterranean Gas Forum’s founding agreement – which was signed by Egypt, Israel, Greece, the Greek Cypriot administration, Italy and Jordan – was not inherently anti-Turkish. The proposed conference would help efforts to transform the Eastern Mediterranean into a “sea of peace and sharing,” whether through the allocation of energy reserves or broader economic cooperation.

The Mediterranean, a cradle of civilizations, must cease to be a global flashpoint and a center of military buildup. Turkey will remain a major power at the intersection of Europe, North Africa and the Middle East. Unless the Turks have a seat at the negotiating table, those waters won’t calm down.

Let us hope that European leaders do not buy into the naivete of people like Germany’s former ambassador to Ankara, Martin Erdmann, who urged the EU to “wait until Erdoğan runs out of breath.” Neither Erdoğan nor Turkey will run out of breath. Europe would be wise to use the current window of opportunity.

This article was first published by Daily Sabah on September 26, 2020.