NATO, terrorism, Turkey: Who should persuade whom?

Ankara’s only condition is that Sweden, Finland and NATO members do not participate in campaigns that threaten Turkey’s security, such as supporting PKK/YPG terrorists.

Sauli Niinistö and Magdalena Andersson, Finland’s president and Sweden’s prime minister, rushed to Washington, where following a trilateral meeting, United States President Joe Biden recalled NATO’s open-door policy and strongly endorsed the two nations’ membership bids.

It does make sense for the political leaders of Finland and Sweden to ask NATO’s most prominent member for its support. However, their first visit should have been to Turkey to persuade Ankara to lift its veto.

In recent days, Finland has issued a series of more reasonable statements, whereas the Swedish Social Democrats have defended themselves and argued that their government’s support for the PKK terrorist organization is “disinformation,” – which shows that they are yet to appreciate the situation.

Notwithstanding the detailed information Turkey’s security officials have shared with their counterparts, a quick look at the Foundation for Political, Economic and Social Research’s (SETA) report on the PKK presence in Europe – specifically, the chapter on Sweden – would suffice to grasp that country’s aggressive and hostile policy vis-a-vis the PKK and its Syrian component, the YPG.

Terror at center

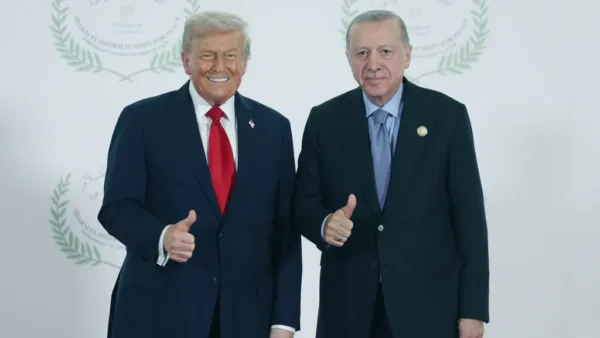

Western media outlets keep reporting that NATO’s most prominent members will “persuade” Turkey to lift its veto. It is possible to imagine that Niinistö and Andersson, too, have asked Biden to persuade President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. That approach, however, won’t contribute to the resolution of NATO’s current crisis. Indeed, Ankara stresses that Stockholm and Helsinki must be persuaded. Keeping in mind that Washington’s own policy on the PKK/YPG and Gülenist Terror Group (FETÖ) remains disastrous, how could it be expected to vouch for Sweden and Finland? Is Ankara expected to accept that?

Turkey has a set of concrete demands: The extradition of 30 known terrorists, the cessation of support for the YPG and that the two countries prevent PKK fundraising, propaganda and recruitment efforts within their borders. To ignore those demands with reference to democracy and the rule of law gets us nowhere.

Let everyone remember that supporting the fight against terrorism is a common policy among democracies as well as NATO allies.

In response to the Turkish objection, some frequently point to the United States, Germany and other members of the European Union pursuing equally negligent and aggressive policies regarding the PKK and FETÖ. Indeed, Ankara experienced tensions with those countries in the past over their relevant policy choices.

Now that Turkey has the right to veto NATO’s expansion, does it deserve to be criticized for using that power to encourage Finland and Sweden to revise their policies for the solidarity of the NATO alliance and the spirit of the partnership? Or should those two nations, which Turkey – NATO’s second-largest military – will have to defend under Article 5, be told to stop supporting terrorism?

To depict the current situation as Erdoğan blackmailing NATO, dragging his feet or gambling does not serve to strengthen the Western alliance. Indeed, the claim that “the current situation pleases Russian President Vladimir Putin” reflects the lack of understanding of Turkey’s intra-NATO security concerns.

What’s the aim?

If the new geopolitical atmosphere that the Russian invasion of Ukraine ushered in requires the swift admission of Finland and Sweden, NATO’s leading members ought to persuade those governments to address Turkey’s righteous demands. They need to tell Stockholm and Helsinki that their stubbornness hurts their own interests as well as NATO – not the other way around.

Some Western commentators also say that Erdoğan made this latest move with an eye on next year’s election in Turkey. For some reason, they do not (want to) understand that the Turkish president would have faced criticism at home had he not taken this particular step. Perhaps those Western commentators get that impression from the opposition’s silence regarding this national question.

Having spent 20 years negotiating with a range of Western leaders, Erdoğan taps into his experience. He communicates Turkey’s concerns to its allies and looks out for his country’s security interests. That is all there is.