Tehran, Jeddah summits and regional dynamics

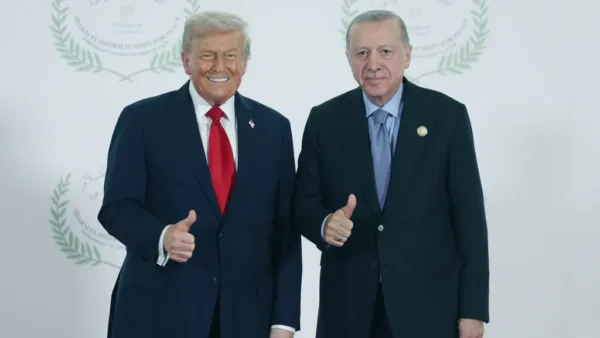

Two summits in Jeddah and Tehran held three days apart turned all eyes to the Middle East.

The Western media promptly portrayed the two events as the formation of rival alliances. As a matter of fact, some went as far as describing the Tehran summit as an “axis of anti-Western autocrats.”

That shallow approach certainly fails to appreciate where the world is headed and the region’s new political realities. It would be a big mistake to imagine the regional balance of power as a rivalry between the United States, Israel and the Gulf and Russia, Iran and Turkey.

Obviously, both summits related to more than the security concerns of regional powers. The points of reference, too, hinted at great power competition.

In an attempt to undo Washington’s regional perception as a “receding” power (in the wake of his retreat from Afghanistan), U.S. President Joe Biden did his best to deliver a strong message to the Gulf states: “We will never walk away and leave a vacuum to be filled by China, Russia or Iran.”

It goes without saying that that statement would suffice to defend Israel’s security interests.

It is no less obvious, however, that the Gulf states won’t just try and form an alliance under American leadership before they see a strong commitment from Washington to reengage with the region and figure out what that means in concrete terms.

That Prince Faisal bin Farhan Al Saud, Saudi Arabia’s foreign minister, said that “there is no such thing as an Arab NATO” attested to the regional realities.

Provided that the anti-Iran bloc failed during former U.S. President Donald Trump’s term, the Gulf states may cooperate with Israel on security but it is highly unlikely for that cooperation to morph into an anti-Iran alliance.

First and foremost, the Tehran summit represented the continuation of Russia, Turkey and Iran’s attempts to manage the Syria file through the Astana Process.

For Russia, which became the target of significant Western sanctions upon invading Ukraine, that occasion facilitated negotiations on defense and energy with Iran and on the grain corridor with Turkey.

There is no reason to think that the Russian leader, Vladimir Putin, has any intention of abandoning Moscow’s spheres of influence in the Middle East.

As a country targeted by sanctions itself, Iran, too, needs to cooperate with Russia.

At the same time, Israel’s decision to sanction Russia and attacks on Iranian targets serve to push Moscow and Tehran closer.

However, there is no reason to think that Russia would welcome Iran’s development of nuclear weapons or emergence as the dominant power in Syria either.

Meanwhile, the rivalry between Ankara and Tehran over Syria and Iraq continues.

Ahead of the summit, Iran’s religious leader, Ali Khamenei, opposed Turkey’s imminent military operation in Syria – which was followed by President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan reiterating his commitment to conducting a military operation in Tel Rifaat and Manbij. Those statements demonstrated that the two governments remain committed to their respective positions and have agreed to manage their disagreements.

The Tehran summit’s final communique, which consisted of 16 points, related to Syria’s territorial integrity, counterterrorism cooperation “inclusive of attempts at self-government,” opposing the illegal seizure of oil revenue that belongs to Syria, promoting peace in Idlib, the importance of the Constitutional Committee, the safe return of refugees and the condemnation of Israel’s military assaults in Syria.

That all three nations oppose Washington’s support for the PKK terrorist group’s Syrian wing YPG in the east of the Euphrates river represents the common ground for the Astana Process.

It makes no sense to think of the Jeddah and Tehran summits as “attempts to form rival alliances.”

That view is misguided for three reasons:

First, there are many serious disagreements between those countries, whose representatives met in Jeddah or Tehran and are supposedly trying to form new alliances, on many issues.

Secondly, neither summit featured a great power willing to lead the bloc or regional powers that were on board with that plan.

Furthermore, Turkey opposes the formation of rival blocs, which serve to polarize the region, and argues that such pursuits not only destabilize but also worsen ongoing conflicts in the region.

Indeed, Turkey has pursued normalization with the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Israel and Saudi Arabia over the last two years, which enabled that country to strengthen its bilateral cooperation with the participants of both summits.

Last but not least, all countries in the region are fully aware that the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the Western reaction to that move created a new international atmosphere.

To be continued…