Turkey’s referendum a reaction against the coup tradition

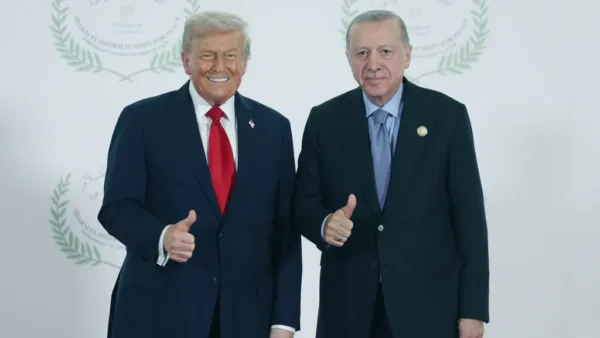

On April 16, 51.4 percent of the Turkish people voted in favor of constitutional reform and Turkey finally crossed the river. For the first time in the country’s history, ordinary citizens changed Turkey’s system of government through democratic means. As both President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and Prime Minister Binali Yıldırım stated, the referendum marks the beginning of a new period in Turkish history, when citizens of all backgrounds must stand together.

It would be very wrong to compare the April vote with previous constitutional reforms, which were forcefully created by the representatives of the coup tradition.

Moving forward, politicians will have an important task: To pass harmonization laws and to manage the transition to a presidential system until the November 2019 elections. There is no doubt that the new system of government will be the centerpiece of President Erdoğan’s legacy.

In order to accurately interpret the referendum results, it is necessary to compare them against the outcome of the 2014 presidential election. At the same time, we must keep in mind that the 1961 and 1982 constitutions had been drafted by coup plotters and therefore cannot be compared with the constitutional reform bill, which was adopted by the people’s elected representatives in Parliament. As such, it would be meaningless to try and compare the April 16 referendum with previous constitutional votes.

There were other constitutional referendums as well: In 1987, 50.2 percent of the electorate voted in favor of lifting the ban on politicians who had been forced out of politics by the 1980 military junta. The following year, then-Prime Minister Turgut Özal had unsuccessfully called for a referendum to call for early municipal elections, when 65 percent of voters denied him the opportunity.

In 2007, following a standoff between the military guardianship regime and civilian politicians over the presidential election, 69 percent had voted in favor of introducing popular presidential elections. Finally, in 2010, 57.8 percent had supported a plan to reorganize the high judiciary. All three referendums that passed, in other words, proposed some amendments to the 1982 Constitution.

By contrast, the April 16 referendum was related to the system of government. As such, it was unlikely from the start that Turkey’s major political parties would all support this comprehensive plan. In 2011 and 2016, Parliament’s failure to facilitate an agreement between the four parties proved that it was impossible to draft a new constitution. In the wake of the July 15 coup attempt, it became possible for enough parliamentarians to support the bill to call for a referendum.

Under the circumstances, it could have been desirable for the vast majority of the population to support the proposed plan to adopt a new system of government, but it would have been out of touch with the country’s political realities. At this point, it is important to recall that the Brexit referendum was actually closer than the April 16 vote in Turkey, even though the issue at hand was much more limited.

Moving forward, the only way to reverse Sunday’s decision will be to create a strong enough majority in the Parliament that is willing to go back to parliamentarism. At this time, however, our priority must be to restructure the executive branch in line with the presidential system.

Again, the only meaningful point of reference for the April 16 referendum would be the 2014 presidential race. Since both races required the winners to gain the support of a simple majority, two major voter blocs emerged in both cases. In the next presidential election, political parties will have to identify candidates around whom their blocs can unite. At the same time, they will have to sync their presidential election strategies with parliamentary elections. Looking ahead, it is safe to assume that the (Justice and Development Party) AK Party-MHP (Nationalist Movement Party) bloc is ahead by a few steps.

President Erdoğan, who led the people’s resistance against the July 15 coup attempt, could presumably win more votes than 51.4 percent in 2019. After all, the “no” campaign knew on Sunday that the president would have remained in power even if the referendum had failed. For the Republican People’s Party (CHP), the Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP) and MHP rebels, the “no” campaign’s ability to win 48.6 percent of the vote could be a source of hope for the future. But they would have to work out a formula to keep the ideologically diverse components of this bloc intact. If they want to succeed, they will need to reconcile the HDP’s Kurdish nationalism with the Turkish nationalism of the CHP base and the MHP rebels.

This article was first published in Daily Sabah on April 19, 2017.