U.S.-Turkey Realignment on Syria

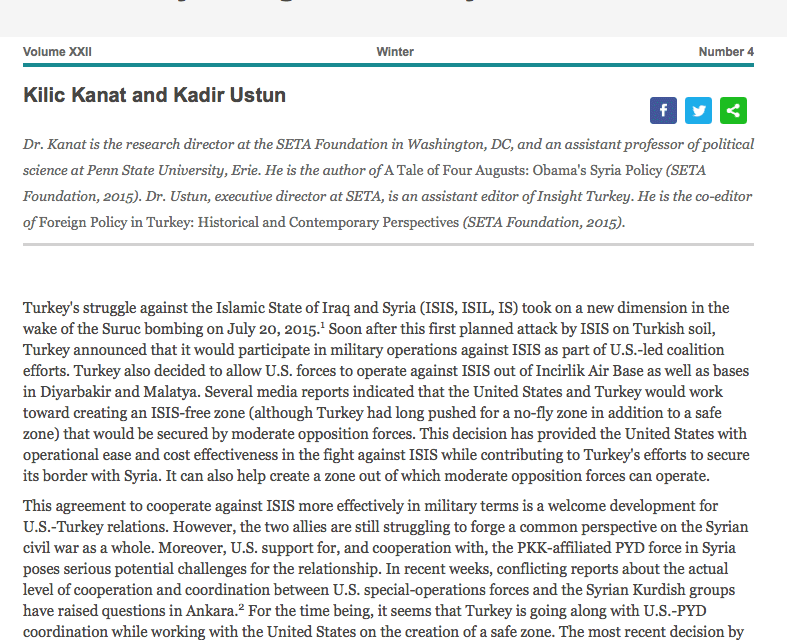

The following is an excerpt from the Journal Essay “U.S.-Turkey Realignment on Syria” published by Kilic B. Kanat and Kadir Ustun in the Winter 2015 edition of Middle East Policy.

Access Full Article Here

Turkey’s struggle against the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS, ISIL, IS) took on a new dimension in the wake of the Suruc bombing on July 20, 2015.1 Soon after this first planned attack by ISIS on Turkish soil, Turkey announced that it would participate in military operations against ISIS as part of U.S.-led coalition efforts. Turkey also decided to allow U.S. forces to operate against ISIS out of Incirlik Air Base as well as bases in Diyarbakir and Malatya. Several media reports indicated that the United States and Turkey would work toward creating an ISIS-free zone (although Turkey had long pushed for a no-fly zone in addition to a safe zone) that would be secured by moderate opposition forces. This decision has provided the United States with operational ease and cost effectiveness in the fight against ISIS while contributing to Turkey’s efforts to secure its border with Syria. It can also help create a zone out of which moderate opposition forces can operate.

This agreement to cooperate against ISIS more effectively in military terms is a welcome development for U.S.-Turkey relations. However, the two allies are still struggling to forge a common perspective on the Syrian civil war as a whole. Moreover, U.S. support for, and cooperation with, the PKK-affiliated PYD force in Syria poses serious potential challenges for the relationship. In recent weeks, conflicting reports about the actual level of cooperation and coordination between U.S. special-operations forces and the Syrian Kurdish groups have raised questions in Ankara.2 For the time being, it seems that Turkey is going along with U.S.-PYD coordination while working with the United States on the creation of a safe zone. The most recent decision by the Obama administration to send 50 U.S. special forces to fight against ISIS3 may prove to be such a complication, as it indicates that the United States is taking its support for the PYD to the next level. Turkey has been clear about its red line vis-à-vis the expansion of PYD forces to the west of the Euphrates.4 This creates a risky situation in which Turkey may conduct military operations against PYD forces while U.S. special forces are embedded with them.

Turkey has worried that arms given to the PYD might fall into the hands of the PKK and be used against Turkey. Since July 2015, when the PKK announced the end of a long-held ceasefire with the state, Turkey has been conducting operations against the PKK across its border with Iraq and threatened to conduct operations in Syria if the PKK finds a safe haven there through its Syrian affiliate, the PYD. The stunning AK Party victory in the November 1 elections puts the ruling party in a stronger position to pursue the PKK across the border, as well as the PYD, if it tests Turkey’s red lines. If Washington and Ankara cannot come to a comprehensive agreement on their strategy toward the Syrian civil war and different groups on the ground, their bilateral relations may face significant challenges in the coming months, rendering coalition efforts against ISIS more complicated and less effective.

TURKEY’S COUNTERTERRORISM STRATEGY

The Suruc bombing was one of the deadliest terrorist attacks on Turkish soil; 33 people were killed and more than 100 wounded. It was not the first time that ISIS targeted civilians and security forces in Turkey. ISIS had threatened Turkey5 and conducted attacks as early as March 2014, when its operatives killed two Turkish security personnel at a checkpoint in a central Anatolian city.6 Following this incident, in June 2014, the Turkish consulate in Mosul was targeted in the most significant hostage crisis in the history of the Turkish Republic: ISIS kidnapped 49 consular personnel including the consul general.7 Just a few days before the June 7 elections, ISIS targeted Turkey once again, this time at a political rally in Diyarbakir.8 Following the Suruc bombing, ISIS continued its attacks against Turkish targets and killed a soldier at the border.9 This led to Turkey’s retaliation in accordance with military rules of engagement. ISIS published threats against the Turkish government and launched a propaganda campaign against Turkey through both broadcast and social media. In a video message in June 2015, titled “The Conquest of Istanbul,” ISIS members called upon Turks to support ISIS. The speaker in the video said, “Altogether and under the orders of Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi… let’s conquer Istanbul, which the traitor Erdoğan works day and night to hand over to crusaders.”10

After each ISIS attack, Turkish security forces carried out operations against the organization, trying to increase border controls and eliminate the recruitment of Turkish citizens. Turkey also tried to stem the flow of foreign fighters and deported thousands of individuals suspected of planning to join ISIS.11 These were, arguably, traditional counterterrorism measures in response to the threat. However, following the Suruc attack, Turkey revised its strategy, adopting a new doctrine to deal simultaneously with all designated terrorist organizations, most significantly ISIS and the PKK. Concurrent with this new strategy, the Turkish government decided to allow U.S. forces to use Incirlik Air Base,12 and Turkish and U.S. fighter jets started to attack ISIS targets. Moreover, although talks about technicalities are still going on, there seems to be tentative agreement on creating an ISIS-free zone for the moderate opposition fighters who could eventually make possible the repatriation of some of the refugees currently residing in Turkey.13 While shouldering the refugee burden and managing the humanitarian crisis on the ground, Turkey has tried to secure its border through counterterrorism efforts. Ramping up the fight against ISIS and reacting to the Suruc bombing have served as catalysts for the revision of Turkey’s counterterrorism strategy.