A reshuffling of the liberal world order

In my previous column, I mentioned how, in three different, but very important, documents on U.S. national security, namely the National Security Strategy (NSS), National Defense Strategy and Worldwide Threat Assessment reports, there is a strong emphasis on the return of the great power rivalry. These documents particularly mentioned China and Russia as the main challengers to U.S. supremacy around the world.

In fact, potential cooperation between China and Russia is mentioned as one of the significant threats for U.S. foreign policy. Of course this is the perspective of the U.S. and it is possible to read most of the decisions given by the U.S. administrations in the last few years in accordance with this changing threat assessment and perception. The decisions to withdraw from Iraq during the Barack Obama administration and the decision to withdraw forces from Syria given by President Donald Trump last December can also be interpreted as being part of a larger strategy of “resetting” U.S. foreign policy to adapt the changing risks for its national interests in different parts of the world. The U.S., indeed, wants to focus on what threatens its economic interest and military posture in different regions instead of spending time, resources and attention to the civil wars and failed states. The U.S. seems very determined to make this shift in its strategy documents.

However, there is one major problem. While the U.S. has expressed its determination to take steps to make this transformation in its foreign policy, the U.S. administration is failing to explain how they will make this change. More than 70 years ago, in the aftermath of World War II when the U.S. took steps to design a new international system, the American administrations made sure that its allies and supporters would not only benefit from but also contribute to this new international order.

In every critical turning point of the Cold War years, the U.S. time and again refers to its alliance network as one of the bulwarks of its strength and commitment. When the Cold War was ending in the new conflicts of the post-Cold War era, the U.S. one more time emphasized building coalitions and finding partners.

In the first Gulf War, for instance, the U.S. had built one of the largest coalitions of the modern world. However in the absence of joint threat perception, this time it depended mostly on ad hoc coalitions, less structural but definitely more flexible. After the 9/11 terrorist attacks, the U.S. one more time preferred to get the support of alliances and coalitions in order to confront terrorist groups. However, with the Iraq War, we started to see increasing skepticism about the perception of the alliances by the U.S.

The unilateral military actions of George W. Bush followed by the unilateral inaction of the Obama administration. The America First approach was also perceived as one of the pinnacles of unilateralism in the world. Today, in the international community, the U.S. is perceived as a declining superpower that wants to abandon its allies and dismantle alliance structure. Fifteen years ago, Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld divided Europe into two parts, “old Europe” and “new Europe,” and today there are reports about President Trump considering leaving NATO.

These developments are generating confusion about the U.S.’ perception of the role of its allies and alliances during the transformation of the orientation of its foreign policy. The burden sharing so far does not go much beyond asking these countries to increase their defense budgets or buying more U.S. weapons. While considering China as the most significant competitor, the U.S. is at the same time spreading uncertainty and unpredictability to its allies in Asia, and considering Russia as the other most important threat for its interests the U.S. administration is shaking the foundation of its alliances in Europe. There is always a rhetorical emphasis on the significance of U.S. allies in the world during the speeches of the members of the U.S. administration, but there are too many contradictions and inconsistencies that made such statements obsolete.

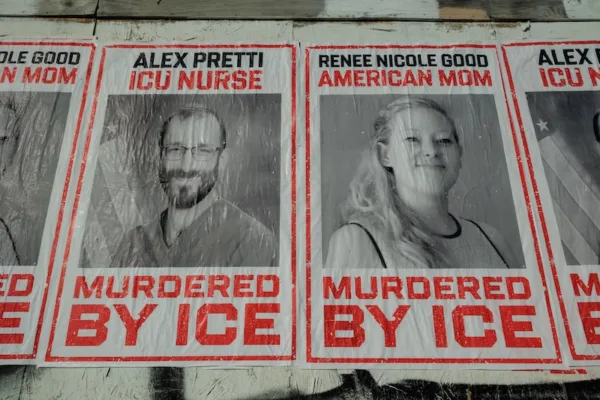

The tour of the U.S. foreign policy leaders in Europe in the last week demonstrated this situation. In Warsaw, the U.S. foreign policymakers fail to form another ad hoc coalition in the Middle East last week. Later in the Munich Security Conference, the U.S. generated a more divided image as the discourse of the administration and some other former leaders in foreign policy displayed two different views of U.S. foreign policy.

At a certain point, it just turned into a reflection of U.S. domestic politics to debates on the transatlantic relations. In fact, the Munich Security Conference in its report mentioned this uncertainty as one of the most critical problems facing international security. The report stated that:

“We seem to be experiencing a reshuffling of core pieces of the international order. A new era of great power competition is unfolding between the United States, China, and Russia, accompanied by a certain leadership vacuum in what has become known as the liberal international order. While no one can tell what the future order will look like, it is becoming obvious new management tools are needed to prevent a situation in which not much may be left to pick up.”

The debates and speeches at the conference reflected this crisis of the liberal international order. But again despite the concerns about the dismantling of this order and risks of the emerging international system, there was no solution offered to find common ground for fixing it. It seems now as if the crisis of the international system is being regarded by the international community, not as a man-made phenomenon, but a natural disaster that is impossible to stop. Everybody in the international community is watching the coming of the crisis as if they are watching the arrival of a hurricane from the weather channel. The only way is to contain the damage the disaster will create. However, there is not even a lot of substantial discussion about it, let alone to discuss the relief efforts after the fallout of the system.

This article was originally published by the Daily Sabah on February 18, 2019.