Clues to comprehend Turkish foreign policy

The Russian invasion of Ukraine continues to reshape the international balance of power. In this new era, Turkey distinguishes itself thanks to its diplomatic activity. Indeed, the country has been so important that the Western media, which constantly refer to President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan as “the sultan,” cannot help but concede that cooperation with Turkey is absolutely necessary. Surely enough, all eyes turned to Erdoğan when the world needed a broker between Russia and Ukraine, someone needed to create a “grain corridor” in the Black Sea and when Sweden and Finland applied for NATO membership.

The Turkish leader, who got his counterparts to accept Turkish demands at the Madrid summit, held a meeting with the Italian prime minister, Mario Draghi, last week. Bilateral cooperation on trade, energy, migrants, Ukraine, grain and the defense industry were on the table. Yet, I spotted some essays in the Italian media that expressed frustration over the positive momentum of Erdoğan’s meeting with Draghi. In truth, I must say that European media outlets seem overwhelmingly jealous of the Turkish president’s ability to capture everyone’s attention in the diplomatic arena. Their comments reflect their unhappiness with the fact that a player, which they’d like to be excluded, came to play a defining role in Europe’s security and welfare. That interpretation, however, invariably suffers from a failure to appreciate the strategic thinking behind Turkish foreign policy.

Ironically, Turkey’s opposition parties, too, suffer from that same problem.

Erdoğan has been actively monitoring for two decades where the international system is heading and has taken initiative. He proved able to negotiate with four U.S. presidents and a number of European politicians, who would be difficult to rank.

Again, Erdoğan maintains a special relationship with Russian President Vladimir Putin. It is no secret that Turkey has been confronting Russia in many areas, where their interests clash, in recent years. Syria, Libya, Karabakh and Ukraine immediately come to mind. Yet Erdoğan manages to cooperate with his Russian counterpart in many areas, including energy, thanks to leader-to-leader diplomacy. The Western governments find it difficult to make sense of this special relationship. At times, they portray the relationship between Erdoğan and Putin as opposing the Western alliance. At other times, they stress the importance of Turkey’s relationship with Russia for European security – as has been the case with the Ukraine crisis.

Turkey did not get here easily by any means. The country expanded its capacity by coping with the negative side effects of the Arab revolts, the civil wars in Syria and Iraq, Washington’s misguided choices in Syria, the European Union’s isolation, Russia’s growing footprint in the Middle East and attempts by status quo powers in the Gulf to reshape the region.

That capacity covers humanitarian aid, trade, the defense industry and security cooperation. In other words, Erdoğan is not showing off in the international arena. He merely taps into 20 years of experience to maximize Turkey’s national interests.

The war in Ukraine rendered Turkey more valuable to Europe’s new security architecture. European politicians would be wise to set aside their obsessions and work with Turkey’s new realities.

Greek Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis is among those politicians that missed that opportunity. In recent years, Greece assumed that it could isolate Turkey in the Eastern Mediterranean by reaching out to Israel, Egypt, the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Saudi Arabia – countries, whose relations with Turkey were strained at the time. It also thought that it could mount pressure on Turkey within the Western alliance by building new defense relationships with France and the U.S. Ankara foiled that plot by adopting a policy of normalization. Furthermore, the Ukraine war highlighted anew Turkey’s strategic importance to the West. Mitsotakis made the real mistake by panicking at that particular moment: Having shaken Erdoğan’s hand and agreed not to let third parties meddle in bilateral relations, the Greek prime minister visited Washington in an effort to block the sale of F-16 fighter jets to Turkey – to which Erdoğan understandably reacted. With both countries heading to elections, it won’t be easy to keep a lid on bilateral tensions.

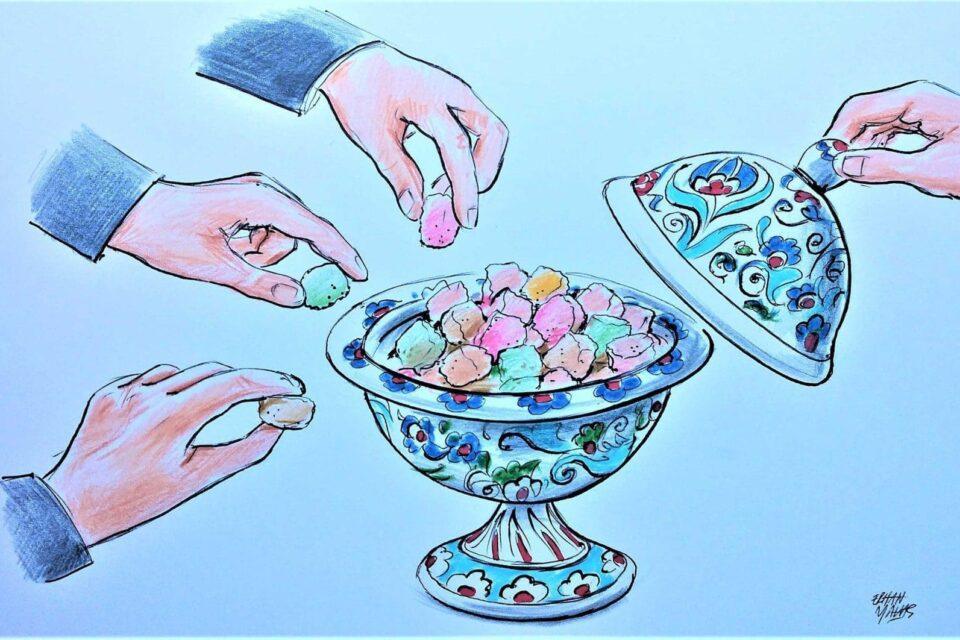

The final clue is about the reality that those countries that are normalizing their relations with Turkey have experienced. Turkey is a country whose friendship and adversity make a real impact. It is also straightforward amid tensions and regarding cooperation. As such, it does everything in its power for others when such needs arise.

The Gulf states have seen how Ankara supported Doha during the Qatar blockade of 2017. Turkey made that same impact on Libya in 2019-2020. Finally, Turkey’s support for Azerbaijan during the Second Karabakh War in 2020 marked the zenith of that impact.

To those countries, with which we are normalizing, those cases demonstrate the true impact and value of Turkey’s friendship.