From Turkey to NATO: An unmissable opportunity

Ankara is not against NATO’s expansion amid the Russia-Ukraine war but objects to Finland and Sweden’s unacceptable policies on terrorist groups

The war in Ukraine put a spotlight on the question of NATO expansion. Some American strategists, including John Mearsheimer, argued that the United States and Europe made a mistake by pushing NATO to Russia’s borders. Some believe that the West’s failure to take that criticism into account caused Russia to attack Ukraine in 2014 and 2022.

Russian President Vladimir Putin also views NATO’s enlargement as a grave threat and uses that development to justify his invasion of Ukraine. As a matter of fact, the Russian leader portrays the West’s (military and other types of) support for Ukraine as proof that his country is actually fighting the West.

It goes without saying that the invasion of Ukraine and the Russian threats have expedited, rather than stemmed, NATO’s expansion. It also seems that the Kremlin’s threats against Finland and Sweden – that “there will be consequences” – will prove futile. As the NATO allies talk about solidarity more frequently, having deployed additional troops to Eastern Europe and delivered heavy weapons to Ukraine, they will look for ways to make the alliance more effective at the Madrid summit next month. The organization will also update its strategic concept for 2030 in light of the growing Russian threat.

Yet all eyes are currently on Turkey, which expressed its concerns over the admission of those two nations – especially Sweden – into NATO and made certain demands.

Turkey’s concerns

First and foremost, Ankara’s concerns are not intended to undermine NATO solidarity. In other words, they have nothing to do with the Russian critique of NATO’s enlargement. Quite the contrary, the Turkish position reflects an attempt to find common ground between the allies’ security (counterterrorism) approaches. Specifically, Turkey wants a more coherent defense policy with more solidarity.

It is quite obvious that Finland and Sweden must revise their policies on the PKK and the Gülenist Terror Group (FETÖ). It was a welcome development that those nations recognized Turkish concerns and expressed a willingness to negotiate. All parties must understand, however, that Turkey won’t be appeased by empty promises.

Russia everywhere

It is only reasonable and fair for Turkey, which was left to face Russia alone during the Syrian civil war and had to deal with terrorist groups and Syrian refugees almost without assistance, to demand certain positive steps from NATO and the relevant states during this new period of potential expansion. Making such arrangements would also contribute to NATO’s integrity and effectiveness. In this sense, it would be a serious mistake for some Western governments to treat Ankara’s objection as a sign that Turkey represents a problem for NATO.

The question why Turkey objects to NATO’s enlargement now, too, is quite meaningless. If the Russian invasion of Ukraine has indeed marked the beginning of a new chapter in the West’s relations with Russia and encouraged NATO’s strengthening, then the rightful requests of Turkey – which faces Russia in many places like Syria, Libya, Karabakh and the Black Sea – ought to be negotiated.

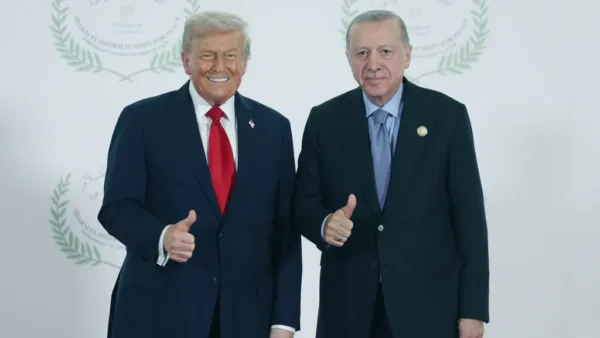

We must keep in mind that crises represent moments to seize new opportunities. President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan thus presents the Western leaders with an opportunity to ensure that NATO becomes an organization that addresses the security concerns of all member states. Instead of engaging in an ideologically-charged debate on Turkey, the Western audiences should focus on that fact.

The Madrid summit in June would be a good opportunity to make that happen.