Questioning normalization with the United Arab Emirates

One can tell how foreign policy dialogue tends to serve individual interests by analyzing how Turkey’s opposition parties question normalization with the United Arab Emirates (UAE). Critics assume that ideology and discourse play a defining role in Turkish foreign policy under the ruling Justice and Development Party (AK Party). In truth, pragmatism and rationality are, without exception, what drives the AK Party’s pursuit of national interests. The ruling party’s policymakers strive to achieve national interests by taking into consideration the balance of power and the ever-changing preferences of the relevant stakeholders. Overall, hostility, competition and cooperation in the international arena are rooted in national interests and determined dynamically, which means discourse has become a tool that one utilizes to get what one wants.

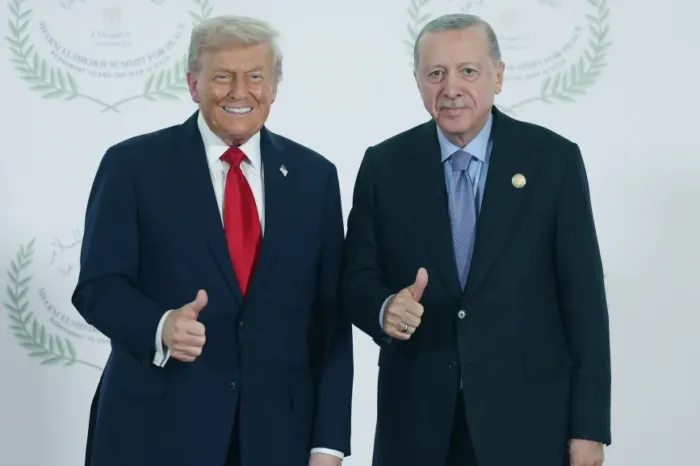

What Turkey’s opposition leaders really dislike is how capably President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has shaped the interaction between foreign policy and domestic politics for 19 years. They take issue with Erdoğan pushing back against rivals with words and, at other times, acting pragmatically with an eye on national interests. To make matters worse, they seem to be infuriated by the president making new decisions at the expense of earlier choices, which the opposition has fiercely criticized. The opposition’s reaction, in turn, pushes it to assume an emotional and irrational position.

In the most recent example, main opposition Republican People’s Party CHP Chairperson Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu, commenting on Ankara’s normalization with the UAE, tried to strengthen his argument by mentioning the Rabaa, a political sign made by raising four fingers and folding the thumb, often used by Erdoğan. “What happened to your Rabaa and your (Muslim) Brotherhood? I keep saying the same thing: Lies and empty perceptions are everything to the (presidential) palace. They will immediately sell out their cause if they stand to make money. True Muslims do not belong together with the palace,” he said.

Let us ignore for a moment that the main opposition leader’s final sentence was an extraordinary example of mixing religion with politics. Some commentators built on Kılıçdaroğlu’s remarks by inquiring about the moral significance of making contact with a country accused of bankrolling the July 15, 2016 coup attempt and its crown prince. Others linked the normalization attempt, which had been in the making for almost one year, to the latest currency shocks and criticized the government for pursuing “economic liberation” with the help of the UAE. Yet others, who are somewhat better at analytical thinking, claimed that normalization with the UAE represented “the end of the Ikhwan (Muslim Brotherhood) and ‘political Islam.’”

What really happened though?

During the Arab Spring, Turkey supported democratically elected politicians and opposed military coups. Egypt’s Mohammed Morsi and Tunisia’s Rached Ghannouchi were two cases in point. It is important to note, however, that Turkey never turned its vocal criticism of military coups into “democracy promotion.” In Libya, the Turks sided with that country’s legitimate government in line with their vested interests in the Eastern Mediterranean. Despite criticizing Gen. Abdel-Fattah el-Sissi’s coup d’etat, Turkey became the last country to send its military to Syria in 2016. Its purpose was to eliminate the PKK/YPG “terror corridor” and create a safe zone for refugees. That is still the case.

For the record, Turkey did not mobilize Arab dissidents, including members of the Muslim Brotherhood, who sought refuge within its borders after their democratic governments were toppled by status quo powers from the Gulf. Obviously, one could not say the same about the other side. Fearing that democratic Islamic parties could transform the Arab world, the status quo powers targeted Turkey and its president. When the Gulf media began attacking Turkey at the time, Erdoğan was portrayed as the champion or poster boy for political Islam.

The actual question is why the other side gave up.

Gulf and beyond

Having managed to get the Muslim Brotherhood listed as a terrorist entity, the Gulf attempted to contain Iran and Turkey – only to watch their ambitious plan to reshape the region go down in flames. At the same time, Turkey’s post-2016 moves in Syria, Qatar and Libya proved to be game-changing. Finally, changes in the U.S. policy toward the Gulf region after President Donald Trump’s departure compelled all players to revise their calculations, resulting in winds of normalization blowing through the region.

The right question, then, could be as follows: Why have certain countries abandoned their opposition to Erdoğan’s policies?

In other words, has the Gulf’s hostility toward Turkey, which it associated with “political Islam,” ended in light of last week’s official visit? Have they conceded that Erdoğan’s regional policy was a success?

Turkey has never pursued a policy that involved meddling in the internal affairs of any country or attacking them. Nor did it hesitate to use its political and military might, in legitimate ways, to ensure its national security. Let us keep in mind that a fresh and rational reassessment of national interests could make tensions between states go away.

This article was first published in Daily Sabah on November 29, 2021.