Turkey’s politics: The case of secularism and Atatürk

There is no shortage of ultra-secularist concerns in Turkey. In recent days, the country’s ultra-secularists expressed concern that two developments could represent “the final nails” in secularism’s coffin: the Taliban’s return to power in Afghanistan and certain practices by the ruling Justice and Development Party (AK Party). Some commentators even see links between those two areas.

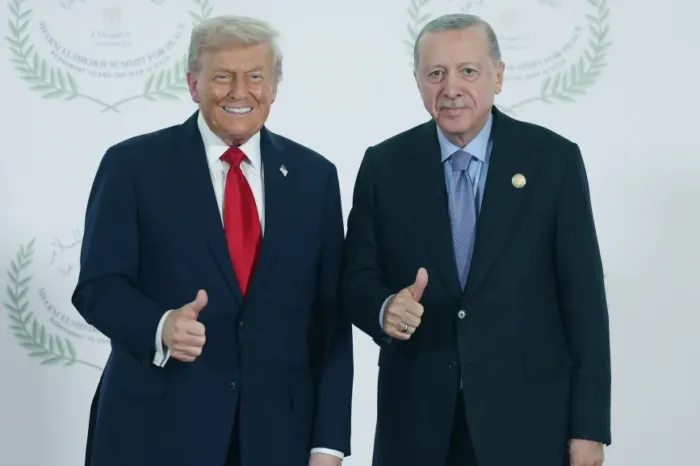

While the world worries about the repression of Afghan women under Taliban rule, some columnists and politicians in Turkey spread fear of potential “Talibanization.” Some of them argue that the arrival of illegal immigrants from Afghanistan will promote a “Taliban-like approach” in the country. Others accuse President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan of having already formed a “Taliban-like government” through his policies, adding that he brought the secular Republic to the “brink of collapse.”

It is self-evident that those concerns are misplaced. The folks who spread those claims clearly disregard the resilience of secular lifestyles and the principle of secular government. To be perfectly clear, Turkey is in no position to come under the influence of religious life in Iran, Afghanistan or Saudi Arabia. Quite the contrary, the Turkish nation has a rich and diverse experience that could seriously influence the citizens of those countries. If anyone needs to worry, it is the governments of Iran and Saudi Arabia, and the Taliban – not the Turks.

Atatürk and the Republic

It is unlikely that the secularism/conservatism debate will play a prominent role in the 2023 election campaign. There is no reason to expect the main opposition Republican People’s Party (CHP), which hopes to win over right-leaning conservatives, to go back to its old, ultra-secularist talking points. However, Muharrem Ince, who recently left the main opposition party, could attempt to tap into ultra-secularist fears over the supposed “collapse of secular government” and the alleged lack of references to Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, the Republic’s founder. Moreover, it is no secret that a significant part of Turkish society has been reluctant to display their ultra-nationalist anger in public – hence the possibility of the CHP appealing to concerned ultra-secularists, indirectly, with references to Atatürk and the Republic. Indeed, some Republicans are already talking about “saving the Republic in its second century.”

I sense that the electorate won’t find that approach particularly appealing. Turkey has made significant progress regarding the normalization of secularism’s implementation and the acceptance of Atatürk by all social groups.

The normalization of the practice of secularism has a long and difficult history. The single-party period’s Jacobin and rigid approach to secular government underwent gradual democratization under the multiparty system. There were infringements on religious freedom following military coups, yet abandoning ultra-secularist and repressive practices has been the general trend.

Back to what?

Undoubtedly, the AK Party deserves most of the credit for the normalization, in the sense that society’s religious demands were met by a democratic and secular system. The public display of certain Islamic symbols and the normalization of religious instruction were products of the president’s political struggle. The latest example of that normalization was Lt. Müberra Öztürk, the Turkish Military Academy’s first graduate to wear the headscarf, receiving her diploma from Gen. Yaşar Güler, the chief of the General Staff.

That process of normalization, which Turkish society overwhelmingly supported, was “securitized” by the main opposition party, the staunchest advocate of ultra-secularism. Especially on the campaign trail, CHP politicians accused Erdoğan’s governments of “turning Turkey into an Iran-like, theocratic state.”

Seeing that ultra-secularism was not popular among voters, the CHP reached out to right-leaning conservatives under Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu. The main opposition thus “accepted” the headscarf – using their partnership with the Felicity Party (RP) as proof – did not object to the Hagia Sophia’s reinstatement as a mosque and came to attend the opening of the new Supreme Court of Appeals headquarters, where Islamic prayers were recited. Going forward, neither ultra-secularist commentators nor their former colleague, Ince, are likely to influence Kılıçdaroğlu’s campaign rhetoric for 2023.

Indeed, the main opposition leader assumes that adopting a “moderate” stance toward devout Muslims is necessary to form a broad, anti-Erdoğan alliance. It is highly unlikely for the CHP or any other party to win votes by talking about Atatürk. After all, that common ground for all Turks cannot be appropriated by the proponents of a rigid, ultra-secularist ideology.

The Republic’s founder represents a core element of Turkey’s national identity that various social groups embrace. Under the circumstances, emphasizing the negative would only create divisions and fuel polarization to hurt the folks that resort to such tactics. Yet the real threat here is the strong, ultra-secularist anger that fuels criticism of even the main opposition party – that thinly veiled hate that alienates religious people and verges on Islamophobia.

This article was first published in Daily Sabah on September 6, 2021