US-Israel Relations in the Trump Era

The purpose of this essay is to reflect on how a Trump presidency will influence the course of US relations with the State of Israel.

The Trump administration is in many respects unique in the annals of American political history. Trump sees himself, in the foreign as well as domestic domain, as a transformational figure, and no doubt many of his supporters expect far more from him than simply business as usual.

While it is often the case that the president has far more flexibility to act in the realm of foreign than domestic affairs, the conduct of US foreign policy in general, and its policy towards Israel and the region in particular, is a reflection of deep-seated interests and concerns that by their very nature suggest slow and incremental change rather than precipitous and fundamental break with past practice of the kind that Trump’s bombast often suggests, and that has proven to be so popular with the American electorate.

A New Look in US Policy?

Insofar as Trump considers his options for a new look in US foreign policy towards Israel, he will confront a dynamic and multi-faceted set of policies based on a core set of time-honored assumptions. These include a basic sense of shared interests and values, highlighted by US support for Israel as “the only democracy in the region”, US backing for Israel’s military and nuclear superiority, shared opposition to an imposed solution to the occupation, and a deep antipathy towards Hezbollah and Iran and their interest in challenging Israeli and American power. These commonalities are widely considered by a broad segment of the US political and policy establishment to be not only the best expression of American values but also to best serve hardheaded America interests.

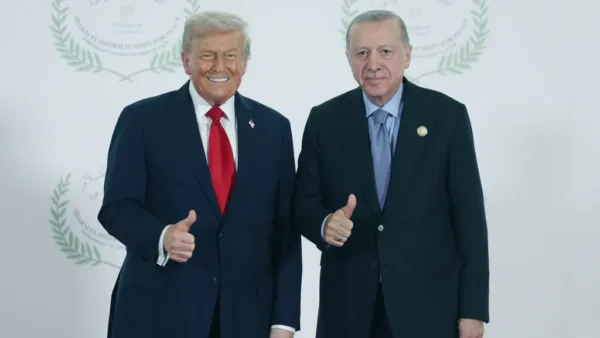

Trump, at his first joint press conference in the White House after discussions with Netanyahu on February 15, observed, “[Israel’s] perseverance in the face of hostility, your open democracy in the face of violence, and your success in the face of tall odds is truly inspirational. . . . Both of our countries will continue and grow. We have a long history of cooperation in the fight against terrorism and the fight against those who do not value human life. America and Israel are two nations that cherish the value of all human life.”[1]

There are not many opportunities for policymakers to congratulate themselves for “doing well by doing good.” Their positive assessment of US policy towards Israel is one.

To observe these sentiments is not to endorse their enduring power and authority, or to critique their many, often-costly shortcomings. It is rather to recognize that policies that Trump has inherited rest upon assumptions that reflect an American consensus, some of which have succeeded and others of which have failed consistently, but all of which nonetheless form an interlocking set of positions that predispose the Trump administration to accommodate as it charts the course of his presidency.

Another critical aspect of understanding policy in the Trump era does not relate specifically to the Middle East, but rather to the new president’s outlook in general.

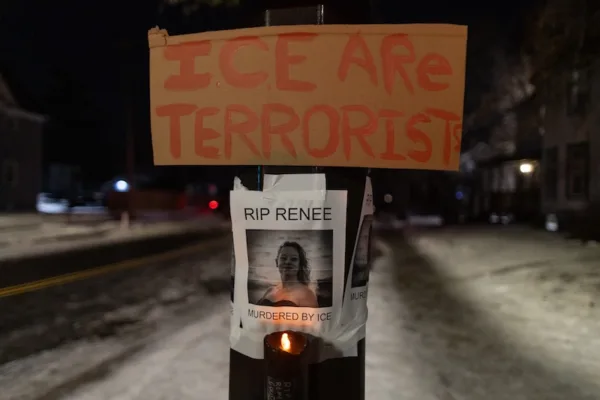

Trump’s promise to “make America great again” represents an authentic response to broad, disturbing failures of the American system and the estrangement many Americans feel from their ruling economic and political institutions.

Trump’s victory represents a popular endorsement of his demand that leaders and institutions be held accountable for the uncomfortable truths that supporters believe he is the only one bold enough to acknowledge – that President George W. Bush failed to protect the US on 9/11; that the war in Iraq was based on a lie; and that traditional politicians – Republican and Democrat alike – are the source of the US’s economic problems and often the obstacle to their solution. Policies relating directly to Israel are notably absent from this list.

Nevertheless, to even suggest such views, let alone see them endorsed, by the “leader of the free world” in the first months of Trump’s rule, has destabilized the broader environment, including Israel, in which foreign policy decisions are assessed and implemented.

Trump’s idiosyncratic style amplifies his populist and often-radical messages across a range of issues. Such pronouncements, which if coming from any of his predecessors would have been considered as the consequence of serious reflection and indicative of a settled redirection of policy, are in Trump’s case often no more than random declarations with no more relevance to policy than a passing summer breeze. This willful undermining of the credibility and significance of the president’s own declarations –by none other than the president himself – adds to confusion and uncertainty about US aims and intentions, with serious implications for the conduct of policy, and not only towards Israel.

In Trump’s case the best counsel may well be to ignore what he says but watch what he does – towards Israel no less than other policy challenges the White House is facing. Then again, Trump may on occasion mean exactly what he says. No one really knows. But one ignores the statements of the president of the United States at one’s peril.

The Future of the Iran Deal

Washington’s policy towards JCPOA is a typical case in point. Iran is at the top of Israel’s policy concerns, and its declared interest in preventing Iran’s ability to manufacture a nuclear weapon is number one on this list. Netanyahu has made no secret of this, or of his unprecedented opposition to President Barack Obama’s signature effort to address this challenge diplomatically.

Donald Trump’s remarks during the campaign and in the White House offer clear encouragement to those like Netanyahu who have yet to be reconciled to the agreement.

“The deal with Iran,” Trump explained in an interview in the Israeli daily Israel Hayom, “was a disaster for Israel. Inconceivable that it was made. It was poorly negotiated and executed. . . . It is too bad a deal like that was made.”

Nevertheless, National Security Council Senior Director for Weapons of Mass Destruction and Counter-Proliferation Chris Ford announced on March 21 a far more measured policy upholding the agreement negotiated by his predecessor.

“Until such time as we have guidance from above to do something differently, our marching orders are very clear…we will ensure that the United States adheres strictly to its limits under the JCPOA, and we will also work very hard to make sure that Iran does,” Ford said during a speech at the 2016 Nuclear Policy Conference.[3]

Trump is certainly not the only president whose actions prove to be far more modest than his rhetoric or for that matter his preferences would suggest. The constraints on a president’s ability to break with past policies are considerable. This is not to suggest that Trump’s declarations about Israel have no import, or that he will prove unable to fulfill his numerous pledges – moving the US embassy to Jerusalem and thus recognizing the disputed city as Israel’s capital to cite one example– but to suggest that the pressures in support of core elements of the status quo are considerable.

US Support for Israel’s Qualitative Military Edge

The heart of the US-Israel consensus is Washington’s financial and technological support for the maintenance of Israel’s “qualitative military edge (QME).” Borne in the aftermath of the June 1967 war, the US is committed to assure Israel’s conventional superiority against any combination of enemies, in part in order to maintain the agreed upon policy of nuclear ambiguity surrounding Israel’s well-developed nuclear weapons arsenal.[4]

In what has become a time-honored ritual, every US administration for the last half century has declared support for this bargain. Most recently, at his first meeting on March 8 with Israel’s minister of defense Avigdor Lieberman, Defense Secretary James Mattis repeated the magic words, reaffirming Washington’s continuing support to “advance the U.S.-Israeli defense relationship” and maintain “Israel’s qualitative military edge.”[5]

For Israel, however, prudence suggests a need to be ever vigilant of changes in US policy or even the hint of a change that may impact not only the relationship but also Israel’s ability to define and preempt challenges to its own national security concerns. Such apprehensions are heightened when any new occupant takes residence in the White House. No matter the long history of intimate collaboration, an Israeli prime minister must remain keenly focused on re-establishing close working relations with the new administration. Notwithstanding the reaffirmation of continuing support for Israel’s strategic superiority, Trump’s unique predilection for making bombastic statements on matters of considered at the heart of Israel’s national security concerns only serves to heighten such apprehensions.

During the campaign and after, Trump’s pronouncements on a range of issues – Jerusalem and a “one state solution” most prominently — have raised both hopes and fears of a dramatic change in US policy – whether towards US recognition of Jerusalem as Israel’s capital or American indifference about the prospect of an agreement between Israel and the PLO. His selection as ambassador of a prominent supporter of Israel’s messianic religious settlement community polarized the Senate confirmation process, injecting an unprecedented demonstration of political partisanship into the US policymaking arena on Israel.[6]

U.S. security and economic assistance to Israel, running into the billions annually, retains a preferred, if not unique position, in Washington’s budgetary allocations. There is no suggestion of a reduction in such support, notwithstanding the new administration’s general support for broad budget cuts in both security and economic assistance.

Iran

“The security challenges faced by Israel are enormous,” Trump has declared, “including the threat of Iran’s nuclear ambitions, which I’ve talked a lot about. One of the worst deals I’ve ever seen is the Iran deal. My administration has already imposed new sanctions on Iran, and I will do more to prevent Iran from ever developing — I mean ever — a nuclear weapon.”[7]

Iran remains high on the list of priorities in both capitals –both because of opposition to the JCPOA and more broadly to opposition to the expansion of the power of Iran and its surrogates in Iraq and Syria. However, the rancor and mutual antipathy that marked relations during the Obama era, in part due to the extraordinary public disputes on JCPOA, have vanished.

Nevertheless, Israel does not share the Trump administrations’ declaration that among the many pressing challenges in the Middle East, “defeating ISIS is the United States’ number one goal in the region.”[8]

Iran remains top on Israel’s list, and an issue that will become more urgent as the endgame in Syria unfolds.[9]

Netanyahu is focused on establishing a working rapport with the new president and his administration. Highlighting if not exaggerating the welcome signals coming from the new team in Washington is a predictable element of this effort.

“[C]hallenging Iran on its violations of ballistic missiles, imposing sanctions on Hezbollah, preventing them, making them pay for the terrorism that they foment throughout the Middle East and beyond, well beyond — I think that’s a change that is clearly evident since President Trump took office,” explained Netanyahu during his visit to Washington in February 2017. “I welcome that. I think it’s — let me say this very openly: I think it’s long overdue, and I think that if we work together — and not just the United States and Israel, but so many others in the region who see eye to eye on the great magnitude and danger of the Iranian threat, then I think we can roll back Iran’s aggression and danger. And that’s something that is important for Israel, the Arab states, but I think it’s vitally important for America . . . So, this is something that is important for all of us. I welcome the change, and I intend to work with President Trump very closely so that we can thwart this danger.”[10]

Trump’s tough talk against Iran has yet to dislodge the essential elements of the policies – on the JCPOA, Iran’s role in Iraq and Syria, and maritime incidents in the Gulf, put in place by his predecessors. At this early point in his tenure, Trump’s policies towards Iran, notwithstanding the US cruise missile attack on a Syrian airbase in early April, are a work in progress, maintaining until now the pace and direction of the Obama years.

Recognition of Jerusalem as Israel’s Capital

For many years, it has been a political ritual in the United States for presidential candidates and members of Congress, Democrats and Republicans alike, to declare an ironclad intention to move the US embassy to Jerusalem. Everyone knows full well that the occupant in the White House, whether Democrat or Republican, will continue to refuse to do so for well-considered matters of policy and national interest. As in so many respects, however, Trump may be different.

Trump tread a well-worn path on this issue during the campaign, declaring to the American Israel Public Affairs Committee in March 2016, “We will move the American embassy to the eternal capital of the Jewish people, Jerusalem. The Palestinians must come to the table knowing that the bond between the United States and Israel is absolutely, totally unbreakable.”[11]

Netanyahu, more than many of his colleagues in his cabinet or on the coalition benches in the Knesset, is skeptical about the value of such declarations. It is notable that the embassy/recognition issue has hardly featured in his policy dialogue with the new president during the first months of 2017, in contrast to Netanyahu’s declared interest in Trump recognizing Israel’s sovereignty over the disputed Golan Heights – a topic he raised during their summit in February. Indeed, an explosive move of the US embassy to Israel’s declared capital is the last thing Netanyahu, who is trying to stitch together a working coalition with Arab states, needs at the moment.[12]

Trump, as president, readily acknowledges complexities that as a candidate he ignored,”I am thinking about the embassy, I am studying the embassy [issue], and we will see what happens. The embassy is not an easy decision. It has obviously been out there for many, many years, and nobody has wanted to make that decision. I’m thinking about it very seriously, and we will see what happens.”[13]

Indeed.

What could very well happen is that Trump’s ambassador to Israel could decide to reside in Jerusalem and establish an office in the city, in the American consulate in West Jerusalem, from which he could conduct official business. Such an action would bring Washington an incremental but significant yet deniable step closer to an operational, quasi-official recognition of Israeli sovereignty in Jerusalem.

Settlements

The settler population of the West Bank and East Jerusalem now numbers close to 700,000. The only effective constraint on Israel’s settlement expansion is territorial withdrawal from the West Bank. This is the simple lesson of history during almost fifty years of occupation, whether in Sinai, evacuated by Menachem Begin in 1982 or the Gaza Strip, evacuated by Ariel Sharon in 2005. Every other attempt to limit or to “freeze” settlements, including constant if ineffective badgering during the Obama years, has fallen woefully short of its objective.

Nevertheless, the Trump administration appears to have stumbled, for reasons that are not at all clear, into a debate with Israel about settlements without even the flawed conceptual focus that his predecessor lacked.

It is certainly the case that neither Israel nor Washington wants to focus their relationship on an issue that, given the constraints on both sides, will never result in a mutually satisfactory conclusion. In their first summit, and then in subsequent talks in Jerusalem and Washington, the new administration and Israel have engaged in a merry go round of discussions on constraining settlement expansion that resemble the familiar and always unrealized dialogue of previous administrations.

There are solid reasons why both parties prefer to declare victory and move this issue off the agenda. Discussions with Washington that center on how Israel, in the words of the new president, can “hold back on settlements a bit” are certainly not an Israeli preference. This is particularly the case given hopes in Israel that Trump’s election would fuel an explicitly annexationist agenda, including the extension of Israeli law and jurisdiction to settlements around Jerusalem or even to the outright annexation of the West Bank itself.

But a diplomatic focus on settlements is nevertheless a dialogue with which Netanyahu is intimately familiar – having personally engaged in such discussions with a series of US envoys over the last two decades. In this important sense, a diplomatic focus on settlement limits is familiar and thus manageable territory, at least for Netanyahu, whose parameters, dangers, and range of potential solutions are well enough known. Far better for Netanyahu that Trump spend his energies on this aspect of Israeli policy, if only as a vehicle for encouraging Arab participation in a broader anti-Iranian coalition, than a serious US initiative that threatens the maintenance of Israel’s security and territorial control of the West Bank and East Jerusalem.

Admittedly, this explanation for the surprising centrality of the settlement issue during Trump’s first months may impute more coherence to the policy than reality warrants.

Settlements are at the heart of Israel’s policy of “creating facts” on the ground – the heart and soul of a policy of hostile occupation that is approaching its 50-year anniversary. It is unlikely that Netanyahu would agree to pay with the coin of settlements for the dubious advantages suggested by a more overt if not necessarily effective understanding with Arab states on the threat posed by Iran.

By any measure — operational or diplomatic – the policy of preempting through civilian settlement the ability of the Palestinians to control territory thus marginalizing their ability to create a sovereign space under their exclusive control – has been remarkably effective and resilient. Even if the Trump administration was committed to undoing this process – and the evidence until now suggests that it is not – a successful challenge to this enterprise is not for the faint of heart, or for a president whose operative policy guidance is often “Let’s see what happens.”

Two states – One state

There are three elements to Trump’s evolving policy towards the ever-elusive agreement between Israel and the PLO on the future of the West Bank and Gaza Strip.

The first is Trump’s basic interest in a “deal” between the parties and indeed the attraction of an “even bigger deal” between Israel and Arab states. The particular elements of such a “deal” appear less important to this president than they were to any of his predecessors.

The Saudi Plan of 2002 offers conditions for a broad rapprochement between the Arab and Muslim worlds and Israel that centers on the creation of a Palestinian state. In parallel, it is suggested that a shared distaste for Iran establishes a common Arab (Sunni) strategic interest with Israel, if not in an agreement on Palestine, then in building a coalition against a “Shia arc” centering on Iran and Hezbollah.

Netanyahu has evidently successfully introduced this “outside-in” formulation– building such a coalition as a gateway to an agreement on Palestine — to a sympathetic Trump White House. But Israel is interested in expanding its relations with Sunni Arabs not to increase pressure upon it to leave the West Bank but rather to further cement its hold on it. It has no interest in paying with West Bank coin the price of an anti-Iranian coalition with Saudi Arabia et al.

Trump is a dealmaker, as he himself tirelessly boasts, and this includes Palestine. The shape of the deal — one state or two — is evidently of far less concern to him. In some respects, his willingness to endorse whatever deal is acceptable to the parties reflects longstanding US policy. His breezy dismissal of the two-state option as the goal of US policy however represents a clear break with recent US goals. And there is no doubt that this ambivalence encourages Netanyahu to refrain from explicitly endorsing the creation of a Palestinian state as a preferred option for Israel.[14]

Trump’s off the cuff dismissal of the centrality of the two-state solution as US policy has whetted the insatiable appetite of Israeli annexationists and increased fears of those who worry about the consequences of a vacuum in not only the mechanism but also the goals of Israel-Palestinian peace talks. US support for a Palestinian state in any form is however, of relatively recent vintage, and Israel’s tentative embrace of this formula is newer yet. In practice, for almost half a century Israel’s policy of occupation and settlement has proceeded in the teeth of ineffective, inconsistent American opposition, while at the same time the strategic relationship has gone from strength to strength.

New Elements on the Agenda

In the first months of Trump’s tenure, US-Israel relations have focused on the following policy areas:

- A shared understanding about Israel’s QME and the strength and intimacy of defense and strategic relations, especially missile defense.

- A shared strategy of constraining Iran’s nuclear and missile capabilities and rolling back the expansion of its regional influence.

- The related effort to mobilize an anti-Iranian coalition that includes Israel and Arab states, and the use of progress on the Israel-Palestinian front, with a focus on settlement restraint, as an instrument in this broader effort.

Unanticipated developments, however, have a way of forcing their way onto the Washington-Israel agenda:

Syria

Syria looms large in this regard. The war in Damascus features no shortage of explosive elements of critical interest in both capitals. Israel-US coordination on Syria has taken a back seat to intensive Israeli efforts since September 2015 with Moscow to establish operational protocols that recognize the essential interests of each party.

As the beginning of the end of the war unfolds a new sense of urgency to establish new “rules of the game” has already led to new forms of armed confrontation between Washington and Syria as well as between Israel and Syria, and introduced Moscow to the problems it faces in reconciling competing Israeli, Syrian, Iranian, Turkish, and Hezbollah goals.

Washington, notwithstanding its demonstrative missile attack, will have a difficult time dealing itself back into effective leadership of the war, but as the Syria, endgame unfolds it is not at all unlikely that Washington and Israel will be confronted with policy and operational challenges that best be anticipated.

Lebanon

Lebanon offers a related if separate set of potential challenges that include a growing dispute over the maritime border (and lucrative gas deposits) between Israel and Lebanon that defied solution despite efforts of the Obama administration to forge a compromise. The uneasy standoff between Israel and Hezbollah threatens to metastasize into a national dispute between Israel and Lebanon if the conflict on maritime rights, or Hezbollah’s and Iran’s effort to secure a place in post-war Syria, intensifies. Washington’s sympathies with Israel in this domain will be tested in the event of a conflict that results in an Israeli war not only against Hezbollah but also against the state of Lebanon itself.

Egypt

In Egypt, more specifically the Sinai Peninsula, the government of president Abdul Fattah al-Sisi is fighting a protracted, asymmetrical war against IS-affiliated militants. Israel and Egypt are cooperating in an unprecedented manner to defeat this threat, but the potential for an Israeli decision to intervene more decisively in Sinai cannot be discounted.

In addition, the US-led MFO contingent has for the most part been able to insulate its forces from this conflict. Both Israel and Egypt see continuing value in the MFO’s continuing operation, which Washington has been prepared to accommodate. But an attack on MFO forces would quickly catapult the issue of the US deployment and the broader question of the US commitment to the Israel-Egypt peace treaty to center stage.

Conclusion

The first months of the Trump administration have offered a clear contrast between pre-election promises and post-election execution. Some campaign promises threatened to recast established diplomatic and security pillars of US policy, and were welcomed with great anticipation by the Netanyahu government and its allies.

President Trump’s policies towards Israel are still very much a work in progress. There has been no wholesale repudiation of settled principles on Jerusalem, Iran, and the occupation that featured prominently during the campaign. It is not at all clear Trump has an interest, or will find himself compelled, to champion broad revisions of policies that he has inherited.

Israeli officials, like many others, understand that this new American administration– no matter how suggestive Trump has been of dramatic changes in US policy — must in the end be measured by the degree to which his pronouncements reflect a considered policy initiative or are merely an emotive response to the needs of the moment. This makes for an unsettling requirement to decipher the true direction of US policies in the Trump Administration – a challenge that has only just begun.

[1] Donald Trump and Benjamin Netanyahu, “Remarks by President Trump and Prime Minister Netanyahu of Israel in Joint Press Conference” (Washington, D.C.), The White House, 15 February 2017, https://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2017/02/15/remarks-president-trump-and-prime-minister-netanyahu-israel-joint-press.

[2] Boaz Bismuth, “’I won’t condemn Israel, it’s been through enough,’” Israel Hayom, 10 February 2017, http://www.israelhayom.com/site/newsletter_article.php?id=40265.

[3] Elad Benari, “Trump to adhere to Iran deal,” Arutz Sheva, 22 March 2017, http://www.israelnationalnews.com/News/News.aspx/227084?utm_source=activetrail&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=nl.

[4] William Wunderle and Andre Briere, “Augmenting Israel’s Qualitative Military Edge,” Middle East Quarterly, Winter 2008, pp. 49-58, http://www.meforum.org/1824/augmenting-israels-qualitative-military-edge.

[5] Jeff Davis, “Readout of Secretary Mattis’ Meeting with Israeli Minister of Defense Avigdor Lieberman,” U.S. Department of Defense, 07 March 2017, https://www.defense.gov/News/News-Releases/News-Release-View/Article/1105891/readout-of-secretary-mattis-meeting-with-israeli-minister-of-defense-avigdor-li.

[6] Donald Trump and Benjamin Netanyahu, “Remarks by President Trump and Prime Minister Netanyahu of Israel in Joint Press Conference” (Washington, D.C.), The White House, 15 February 2017, https://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2017/02/15/remarks-president-trump-and-prime-minister-netanyahu-israel-joint-press.

[7] Donald Trump and Benjamin Netanyahu, “Remarks by President Trump and Prime Minister Netanyahu of Israel in Joint Press Conference” (Washington, D.C.), The White House, 15 February 2017, https://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2017/02/15/remarks-president-trump-and-prime-minister-netanyahu-israel-joint-press.

[8] Rex W. Tillerson, “Remarks at the Ministerial Plenary for the Global Coalition Working to Defeat ISIS” (Washington, D.C.), U.S. Department of State, 22 March 2017, https://www.state.gov/secretary/remarks/2017/03/269039.htm.

[9] Geoffrey Aronson, “Netanyahu to Putin: Keep Iran Away from Golan,” The Middle East Institute, 14 March 2017, http://www.mideasti.org/content/article/netanyahu-putin-keep-iran-away-golan.

[10] Donald Trump and Benjamin Netanyahu, “Remarks by President Trump and Prime Minister Netanyahu of Israel in Joint Press Conference” (Washington, D.C.), The White House, 15 February 2017, https://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2017/02/15/remarks-president-trump-and-prime-minister-netanyahu-israel-joint-press.

[11] Sarah Begley, “Read Donald Trump’s Speech to AIPAC,” Time, 21 March 2016, http://time.com/4267058/donald-trump-aipac-speech-transcript/.

[12] Michael Wilner, “Trump Turns Noncommittal on Jerusalem Embassy Move,” The Jerusalem Post, 23 January 2017, http://www.jpost.com/Israel-News/Politics-And-Diplomacy/Trump-turns-noncommittal-on-Jerusalem-embassy-move-479389.

[13] Boaz Bismuth, “’I won’t condemn Israel, it’s been through enough,’” Israel Hayom, 10 February 2017, http://www.israelhayom.com/site/newsletter_article.php?id=40265.

[14] Donald Trump and Benjamin Netanyahu, “Remarks by President Trump and Prime Minister Netanyahu of Israel in Joint Press Conference” (Washington, D.C.), The White House, 15 February 2017, https://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2017/02/15/remarks-president-trump-and-prime-minister-netanyahu-israel-joint-press.

[15] Nati Yefet, “Lebanon: Israel’s maritime zone law means war,” Globes, 23 March 2017, http://www.globes.co.il/en/article-lebanon-israels-maritime-zone-law-means-war-1001182282.

Geoffrey Aronson is a writer and analyst, specializing in Middle East affairs. Aronson is chairman and co-founder of The Mortons Group. For more than 4 decades, he has been engaged as a commentator and participant in key political and security issues in the Middle East. He consults with a variety of public and private institutions dealing with regional political, security, and development issues. He was the director for Foundation for Middle East Peace and the editor of the bimonthly Report on Israeli Settlement in the Occupied Palestinian Territories until June 2014. He is the author of the following two books: From Side- show to Center Stage: US Policy towards Egypt and Israel and Palestinians, and The Occupied Territories: Creating Facts in the West Bank.