Eye on the sky: The strategic potential of Türkiye’s Steel Dome

When Türkiye’s defence Industry Executive Committee, the key body overseeing the sector, announced the military project, the Steel Dome, last week, it marked a momentous milestone for the country’s defence capabilities.

In an official statement, the Directorate of Communications described the Steel Dome as an initiative to develop a comprehensive layered air defence system.

Haluk Gorgun, the Secretary of Turkish Defence Industries, clarified that the project’s main goal is to ensure that all sensors and weapon systems work together in an integrated network, creating a unified air defence system with real-time operational capabilities. He also said that the system will use artificial intelligence to assist decision-makers.

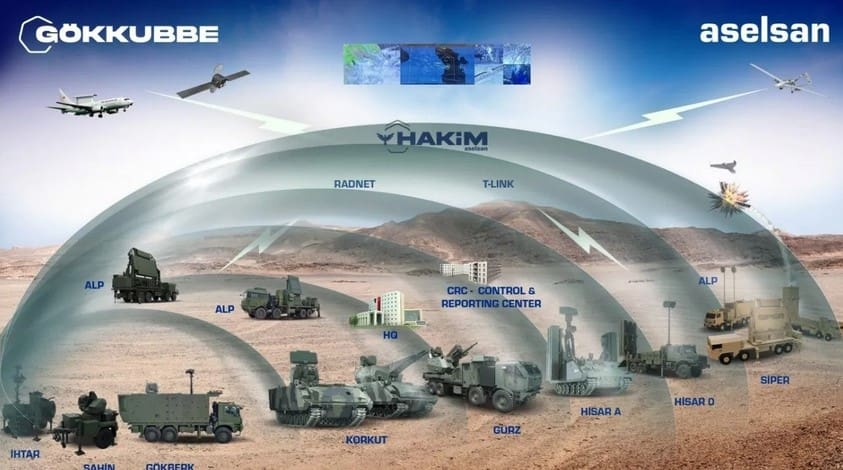

The project will enable seamless operation of various air defence systems developed by the country’s burgeoning defence industry, including KORKUT, HİSAR A+, GÖKBERK, HİSAR-O, and SİPER.

Alongside weapon systems, the Steel Dome will integrate radar and electro-optical technologies, enabling precise tracking, identification, and classification of targets under a unified entity.

The Steel Dome is a sophisticated framework which marks an important milestone in Türkiye’s domestic defence industry journey.

The system is not a final destination but rather a continuously evolving system. It will be perpetually optimised, incorporating new technologies and capabilities as they emerge.

Türkiye has already produced major components of the Steel Dome. Yet, as officials emphasise, it is a system of systems that requires substantial effort to realise fully.

There may be roadblocks similar to those experienced by complex defence projects such as developing the F-35 fighter jet.

Learning from these examples, Türkiye should be mindful of potential challenges such as delays, cost overruns, and single points of failure. Addressing these issues early can help ensure the project’s success.

Türkiye’s air defence journey

Air defence has long been a significant concern for Türkiye, especially since the Gulf War in the early 1990s when the threat of Scud missile attacks loomed large.

In response, the US, Germany, and the Netherlands deployed Patriot missile systems to Türkiye under NATO’s aegis. This practice continued, with NATO providing missile defence systems to Türkiye as needed.

Over time, Türkiye came to view the fulfilment of its air defence requirements as a litmus test of its allies’ understanding of the country’s security concerns.

In the last two decades, Türkiye grappled with heightened geopolitical concerns stemming from regional instability, escalating conflicts, and the increasing visibility of asymmetric threats from both state and non-state actors.

Under these circumstances, Türkiye decided it needed its own air defence systems to develop tailored responses to its unique security challenges.

This would allow the country to protect its airspace independently, without relying on the political decisions of NATO allies, which at times disregarded Türkiye’s security concerns.

In 2006, Ankara launched the T-LORAMIDS (Turkish Long-Range Air and Missile Defence System) programme, aiming to acquire a long-range air and missile defence system.

By 2010, the technical specifications were finalised, and the call for proposals was issued. The programme attracted interest from several international companies: the American firms Raytheon and Lockheed Martin proposed the Patriot system, the French-Italian partnership Eurosam offered the SAMP-T, Russia’s Rosoboronexport put forward the S-300, and China’s CPMIEC suggested the FD-2000 export model.

In 2013, after the US rejected technology transfer for the Patriot missile systems, Türkiye adopted a provisional decision in September 2013 to purchase the Chinese FD-2000 air defence system.

However, by November 2015, Türkiye abandoned the acquisition from China in favour of domestic production. Subsequent discussions about purchasing Patriot systems from the US also failed to materialise.

During this period, Türkiye invested heavily in developing its domestic air defence systems for various altitudes and ranges, such as KORKUT, HISAR-A, HISAR-O and SIPER.

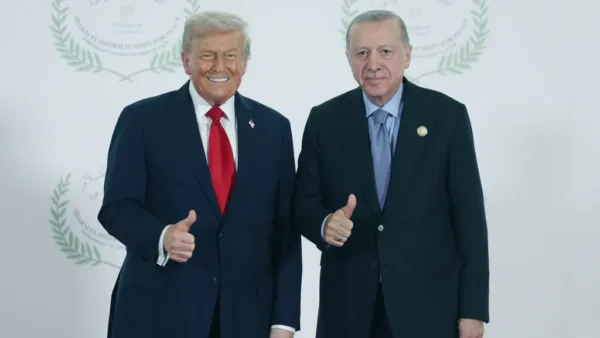

President Erdogan famously remarked, “We will reach the point where we will be able to sell air defence systems to those who, using various excuses, refused to sell them to us.”

The Steel Dome represents the culmination of these efforts.

Integrated air defence system

The Steel Dome is an integrated air defence system (IADS), a network that combines various sensors, weapons, and communication systems to detect, track, and neutralise threats effectively.

Transitioning to an IADS from separate air defence components is a logical and necessary step, as it optimises the operational effectiveness of existing air defence capabilities to address the challenges of the modern battlefield.

An IADS ensures that individual air defence systems work in unison, leveraging each system’s strengths while compensating for its weaknesses. This integration improves response times and minimises coverage gaps.

The integration of various sensors and communication networks within an IADS provides a comprehensive and real-time picture of the airspace. This holistic view is crucial for effectively identifying and prioritising modern air threats, including stealth aircraft and cruise missiles.

Furthermore, an IADS allows for the optimal allocation of defence resources.

Centralising command and control ensures that the most appropriate weapon system is used against each threat, preventing overkill or wasting limited assets.

For example, advanced SAM systems can engage high-value targets, while less expensive and more readily available interceptors might handle lesser threats.

HAKİM, the country’s pioneering air command and control system, will be the backbone of the Steel Dome to perform this function.

Developed entirely by Turkish engineers, HAKİM is built to support and integrate sensor and weapon systems, creating a comprehensive and interoperable air defence network.

This includes new-generation technologies like the RadNet System, EİRS Radar, and the HİSAR and SİPER air defence missile systems.

Similar to NATO’s air command and control system, it can manage early warning radars and fuse radar data to locate, identify and track aircraft.

An additional benefit of IADS is that in a conflict scenario, it ensures that the failure or destruction of a single component does not cripple the network.

The distributed nature of an IADS means that if one radar or missile battery is taken out, others can fill the gap. This resilience is crucial in withstanding saturation attacks and ensuring continuous protection.

Air threats are continually evolving, with adversaries developing advanced technologies such as hypersonic missiles and electronic warfare capabilities.

An IADS can be updated and upgraded more readily than standalone systems, allowing for the integration of new technologies and tactics.

This adaptability ensures that defence capabilities remain relevant and effective against emerging threats.

Challenges of a system of systems

While the Steel Dome, as an IADS, offers numerous advantages, it also embodies the inherent complexities and risks that accompany sophisticated defence systems.

As with any system of systems, the integration of multiple components introduces challenges that must be carefully managed to ensure operational success.

An IADS integrates multiple distinct components—radars, surface-to-air missiles, interceptor aircraft, and command and control centres—into a cohesive whole.

This integration necessitates sophisticated software and hardware interfaces, rigorous testing, and meticulous coordination.

The complexity can lead to issues in interoperability, with each subsystem needing to seamlessly communicate and operate with others.

This was a notable challenge in the F-35 project, a similarly complex defence undertaking, where integrating advanced avionics, stealth technology, and multirole capabilities required extensive troubleshooting and iterative development.

The complexity of integrating such a variety of subsystems often leads to delays. Each component must be rigorously tested, both independently and within the integrated system, to ensure reliability and performance.

Delays in one part of the system can cascade, affecting the entire project timeline. Nevertheless, some components of the Steel Dome are already operational.

The intricate nature of a system of systems often leads to higher-than-anticipated costs.

The need for advanced technology, extensive testing, and iterative development drives up expenses.

The F-35 programme, for instance, is around $180 billion over the original cost estimates. An IADS, with its reliance on advanced sensors, communication networks, and sophisticated command and control systems, is similarly susceptible to escalating costs.

Besides, maintaining an IADS over its operational life can also be challenging and costly. The integrated nature of the system means that any upgrade or repair to one component might necessitate adjustments to others.

An additional challenge is vulnerability to cyber attacks. Integrating multiple components into a single system increases the surface area for potential cyber attacks.

Ensuring the cybersecurity of an IADS requires constant vigilance and updates, as vulnerabilities in one subsystem can compromise the entire network. The F-35 project has faced similar cybersecurity concerns, given its reliance on networked systems and extensive data sharing.

The Steel Dome project is a testament to Türkiye’s growing capability to develop sophisticated defence solutions tailored to its unique security challenges.

However, the project’s success hinges not just on technological innovation but also on strategic planning and foresight.

Anticipating and addressing potential obstacles, such as developmental delays, cost overruns, and cybersecurity vulnerabilities, will be crucial to ensuring the system’s effectiveness and resilience over the long term.